The following is a long, semi-structured rant about parenting.

One of the weird cultural artifacts that I grew up with was a vision of the way people were supposed to raise their children. It was preserved, or to be more accurate, reconstructed, from the era of the 1950s a few decades before. It's still in force today, across large parts of America.

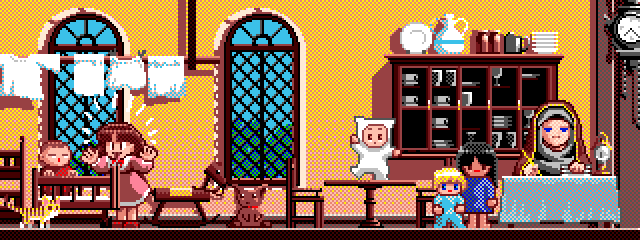

Women were supposed to stay at home and cook and clean and shop and be mothers to the kids, which generally took the form of dressing and feeding them and policing them and being nurturing -- an interesting word with a slippery definition. Men were supposed to have one foot out in the world, working some kind of career in order to bring home money, and their approach to children was more distant, instructive, and punitive. They could teach and protect, but they didn't cook, change diapers, or wipe away tears.

My own parents took this vision and applied modifications to suit their tastes, but still accepted its harshest compromises. For example, both of my parents had established careers before they married but when children started coming along, they could get by on a single income, and my father forcefully argued that since he made more money, he should be the one to keep the job while my mother stayed home. And so, for years, Mom had kids glued to her side all day, until the evening when Dad came home and she could, as she called it, "make the hand-off for a while," which usually meant just a short break before she had to put dinner on the table.

We all have multiple visions of our future clamoring in our heads, and for my mother the battle was intense, because she genuinely loved her work. It stung to have the choice seemingly made for her, not just by my father, but by the expectations of society, acting on that 1950s blueprint. Then there is the additional insult of the wage gap: The choice was only obvious because she was making less money even though they both had the same career. (They were both teachers.)

Over the years, when I've asked her how she felt about this, my Mom has given a range of answers, touching on the different ways it played out. She's said "I was as happy as a clam staying home with you kids; I loved being a Mom," but she's also said "I felt like I was being railroaded when it came to major decisions, and losing my work was one of them. I did substitute teaching but that was much harder."

I didn't become aware of this disconnect between the suburban-ish world I grew up in and the needs of the people who populated it, until I was in my mid-20's and trying to visualize my own destiny, as a romantic partner or a father. At the time I was still ready to buy into the traditional gender role and nuclear family, and if I'd met someone who also bought into it, I think I would have gotten married and had at least one child not too long after leaving college. That would have cemented things. By my reckoning, if that had happened, my kids would be grown and out of the house by now.

Instead I met a series of people who were questioning their future as much as I was, and I developed a strong feeling that traditional parenthood would require me to give up some part of my identity that I wasn't willing to lose. It wasn't something as selfish as "freedom" or "spare time", though there were plenty of people eager to tell me I would lose both. It was all the ways I felt and behaved that didn't fit into the box labeled "suburban American guy". And for decades, though much less so nowadays, the things I liked most about myself were not welcome in that box.

As my romantic journey has continued for all these years I've also met plenty of women who felt the same. In fact, I can now say, with confidence, that I have had a rich and varied dating life well beyond that of most people from my era. And there has no doubt been a lot of self-selection in the partners I stayed with, and the people I only dated briefly, but I have learned there are a lot of women in the world who not only do not want children, but are certain they would make bad parents to their own children or others.

They do not lead lives of loneliness or suffer from a lack of direction. They are often the most accomplished, interesting, and well-rounded people I meet. In part because raising kids simply takes time over the long haul and they're spent that time doing different things, but also because you have to be a bit of an iconoclast at heart just to push that far outside the expectations of your gender. There are still very few narratives for women without children in popular culture even now, rendering these people invisible. It’s as if that vision from the 1950’s is creeping around like a fog, obscuring entire sections of society. Without a cultural scaffolding, this group has had to re-invent itself with every generation, every time as outsiders. Likewise, from the other side of this mirror, women who are parents sometimes find themselves asking, "What else can I be, once this parenting gig settles down and I have time again? Is there anything out there I would be welcome in trying?"

I have intimately known plenty of women who had ambitions to start a family, and then, upon starting one discovered that they were embarking on a war with the infrastructure of society around them, to preserve their individuality. When you have a child, everyone around you, especially other women, suddenly has strong ideas about what you are doing with that child. Especially the amount of attention you are paying to them, and the degree to which you are bending the structure of the rest of your life to do that. Under this lens of judgement you make compromises, between what's expected, what your partner wants, what your child needs, and yourself. The pressure from the outside world is always on the side of the child, and second to that on the side of the partner for the sake of preserving your partnership. Your needs come dead last. Whatever you want to be that doesn’t fit in that box, as woman or man or person, is chopped at until the lid can close.

Pushing back against that pressure doesn't win friends. Doing something for your own sanity that has no visible benefit to your kids doesn't win approval. It’s true that once you have a child, your life generally should not be all about you anymore, but it’s just as true that your life should not be all about the kid, otherwise, why are you bothering?

Faced with the pressure to relinquish their identities, some of the women I know simply cracked under the pressure and wandered away from their children, and the partnership they were birthed into. None of them are proud of this. But for all of them, the choice felt as stark as leave and survive, or stay and die. Wide-eyed people ask, "How could a woman leave her own child?" With luck, those people will never have to learn how. But the frequency of this question illustrates how invisible this group is: No one wants to believe a woman can abandon her kids even in theory.

It seems obvious that if a person knows they won’t enjoy parenting, they should be respected for choosing to avoid having kids, rather than shamed. Less obvious is the need to examine all the frivolous restrictions and baggage that come with parenting, that make the role seem so thankless that people are driven from it.

That weird 1950s stereotype of a woman staying home evolved directly out of a previous situation, where a woman stayed on the farm. She wasn’t somehow insulated from the danger or complication of a career, she was just too damn busy working on the farm like everyone else - which had plenty of its own dangers - and patriarchal power structures like the Catholic Church used the idea of protecting her and protecting the family as an excuse to keep her anchored there. When suburbia came along, with handy slots for appliances and vehicles, the farm miniaturized into a kitchen, and women were transplanted into it, drawn by the promise of convenience.

And if they weren’t comfortable with that transition, there was suddenly something wrong with women. No one blamed suburbia -- it was too convenient and futuristic and safe. You didn't need to slaughter hogs, dig endless rocks out of the soil, chase chickens around a yard, or scare off coyotes with a shotgun. But what you did need to do, since you no longer had land, was make a living somewhere away from the house. And that was really all it took to split men away from women and start the construction of two entirely different pink and blue lives.

So, wind this forward 50 years, and multiple generations of families have organized their entire lives by a collective hallucination of gender roles, which were based almost entirely on that specific convergence of post-agrarian consumer goods and services we call suburbia. The more you stare at it, the more arbitrary and senseless it appears. And as we're all finding out, it's not sustainable. You can't take every child in a generation, break them into pairs along sex lines, and build each pair a single-family home with a garage and a yard connected to a highway system. What's more, why would your children want that by default? Any part of it?

Suburbia wasn’t a step in a progression towards an ideal. It was a massive experiment in standardization, including the standardization of parenting. Things that men and women were supposed to embrace, and project into their children, were invented from whole cloth by advertisers. Even sexuality had a binary range clamped down upon it, with men and women placed on opposite ends, created for - and then reinforced by - the products and stories targeting them.

And of course there's the church. This was a two-handed operation, with consumerism as one hand, and religion as the other. There is an obvious unbroken line, connecting the dictates of a church to go forth and multiply, with the celebration of marriage as a bond that is only legitimate for bearing children, with the unreconstructed desire of parents to compel their own children to reproduce in turn, with the absurd and extremely damaging efforts to punish any social behavior that blurs the imposed gender duality, and reject sexual or romantic behavior that does not directly result in a fertilized embryo and a home for it to mature in. That line is easy to trace, from the heads and books of the colonizers that appeared in America 500 years ago, to the homophobia and hatred of my current day.

Even my own father admitted, late in life, that if I had grown up as gay, or as outwardly effeminate, he would have handled it badly and probably ruined our relationship. "I just know I would have screwed it up," he said. "I wouldn't have understood you."

That was one of the things that deeply bothered me about suburban culture and its emphasis on procreation: The existential panic over men being sexually interested in men, and on top of that the existential panic over men not naturally wanting to stay inside the lane labeled "masculine", which included stoicism and football and beer and cowboy hats and war, but didn't include earrings and heels and caretaking and poetry and whimsy. Who drew these lines? Even my Dad, who was too old to be afraid of most things, only dared to push outside the lines a little. He seemed to have an admiration for those who pushed further, but he personally couldn't. He held a lot of the toxic masculinity of male culture at arms length, shielding me from it in the process, but to him a boy still had to become a man, or he was somehow lost at sea.

More than once I've heard perfectly liberal-seeming parents lament that their children, if they "turned out gay", would be doomed to a life of misery because they would never get to participate in parenthood. Once I was alone with the mother of a woman I was dating, and she confessed that she was glad her daughter was with me, because her daughter was bisexual and "could have just as easily ended up with a lesbian and then I wouldn't have grandkids." To avoid a nasty argument, all I said was, "We'll see," when what I wanted to say was, "Why the hell do you think a lesbian can't be a mother, or even a perfectly good father figure? How many lesbian parents do you know? Or do you think they're such abominations they shouldn't even be around children?"

Sex hormones can be strong, but they don't have the ultimate say in our route to happiness. I've met women who have told me: "My ovaries are screaming at me that I should make little carbon copies of you, but thankfully, they're not in charge." I've also heard: "I'm sex-positive and really into sex, but just the thought of someone putting a baby in me turns me off like a light switch." And I've heard: "Sometimes I get this visceral hunger for the particular smell of an infant. Ever since I smelled it, I sometimes get this ache for it, filling my whole body. Like the thing I want the most in the whole world is a little baby. But, at the same time, children are just terrifying to me and I don't want them around, ever." All these people are threaded into the world, finding their way, and modern culture is still pretending that they're curiosities at best. They all have the same equipment, but because they're not using it to make babies, the classic suburban vision has no place for them.

I’ve met and enjoyed my time with women who were taller than me, hairier than me, louder than me, stronger than me, less nurturing than me, far less interested in children than me, and in some cases significantly more violent than me. Society has labeled them as deviants, and the difficulty they have had is not from being different, but from the label. Many of them are also parents, and have had to struggle to come to terms with the difference between the way they want to parent, and what the world expects. The majority of them are not comfortable accepting a role at the head of a stove, spending their time for years upon years constantly being the sole minder and guardian of infants who are - let’s be frank - terrible conversation, and often quite gross.

Having gotten to know these different people in succession, and understanding how they work, my own perspective about my own role as a parent - or something adjacent to that - has also evolved. I have two sisters with six children between them, and among my closest friends, there are six more children to attend to. I take pride in being an uncle to them, according to a definition of "uncle" that I've had to hammer out on my own, and sometimes the support I provide them is a kind that their own parents are unable to, mostly because they lack perspective, or a necessary amount of detachment. One could say I operate a sort of finishing school for the kids in my life. Their parents let me take them off their hands for a few days, or in some cases, weeks or months. We travel together, we get up to various hijinks, and then I return them with additional perspective. I find it great fun and I have noticed positive changes in the lives of everyone involved.

And meanwhile, society at large is screaming at me that, because I have not impregnated a woman and brought several children to term, and then purchased a single-family home with enough plastic toys and shiny appliances to raise those kids unassisted by friends or extended family, that I am failing my parents, failing society, and failing as a human being.

That voice is much quieter now, even as my own interest in being a parent has slowly grown over the years into the "uncle" role I have now. But it's still there. Sometimes I'm ambushed by this intense loathing for just the physical layout of suburban houses, with their rubber-stamped chunks of lawn and flawless sidewalks, their wall-to-wall carpet, and their giant television sets. The idea of living in such a place fills me with an existential dread. The idea of getting up at 7:00am sharp to drive a car through angry freeway traffic to a building 30 miles away, then reversing the journey at night, makes me want to die. It almost killed me once already. Yes I would do it if there was no other option; if it was a matter of survival. That's what it was for a while. But now that I've found a way to live outside that requirement, I don't ever want to go back. I have come to loathe an existence that revolves around cars.

Assuming it wasn't in that kind of house, the idea of being a stay-at-home Dad, with enough of my own finances sorted out that I wouldn't even need to lean on my co-parent, seems appealing to me. The loss of free time and of my identity through my career would be difficult and I would certainly feel adrift because of that, but I get the feeling I would compensate by pouring energy into the kids. But then the feeling of suburban isolation crowds around this vision and starts to strangle it. My siblings and friends are too geographically scattered to help or keep me company, and without the ability to go where they are, how long could I remain alone with a few beings who are - as I mentioned - terrible conversation and often quite gross, before I start to go crazy?

It baffles me that people consistently tell me that their happiest family memories come from times when the extended family was involved, whether for a holiday, or a vacation, or just an extended visit, and yet we have all convinced ourselves, that the only true route to creating the next generation is to hide exactly two people in their own structure, with a collection of personal appliances, located in some arbitrary location anywhere in the country regardless of how far it is from uncles, aunts, grandparents, and so on. As if, sure, it takes a village, but any old village will do, and what matters is the house with the fence and the driveway, not the presence of diverse and loving people who know your collective history and have charted a dozen different paths to happiness that you can draw from. Paths that include being an aunt or a godmother and so on, when not a parent directly.

Organizing society around the individual has a balance of pluses and minuses, but organizing society around the nuclear family seems to have a lot more in the minus column. If the definition of the family stops at the border beyond parent and child, we all make decisions by only considering the consequences up to that point, and the rest is easily pruned. If dad can make more money in a city 100 miles west, then clearly the wife and children should move, regardless of whether grandpa or grandma or aunt or uncle will remain close enough to be involved. Because more money means better appliances in the better house. This is the math people use in this nation of immigrants, where family legacy is often very short and there may seem like there isn’t even anything to preserve.

My own family was split apart by the pursuit of opportunity in distant parts of the state. My extended family suffered this fate to a lesser degree. Parents worked hard and drove great distances and arranged elaborate schedules to get the kids to socialize together, and it had a significant effect, but even a distance of five or 10 miles, just sufficient such that a car, and therefore an adult and a plan, needs to be involved, is enough of a wedge to split an extended family permanently into pieces, especially over the long haul of many years through adolescence and teenager-hood. I have lots of cousins and second cousins all over the state, but closer to the truth would be to say I had them, and comfortable silence eventually has become silence. I don’t think I would even recognize them on the street anymore. Or their kids -- most of whom are in college at least.

If being a parent means accepting this status quo, it's right to rebel against it. What if being a parent could mean helping to raise children that you didn’t give birth to or stick your genes in? What if supporting other parents was recognized as an important role worth acting to preserve in social structures? The term "godmother" has a religious origin, and is about taking responsibility for the religious education of a child. What if it meant more? What if taking an active role in the lives of your relatives' children as teenagers, even if you don’t like babies, had a name? All these options exist of course, and are taken up by a significant chunk of society, but they are nameless. They are vaguely seen as nice to have, but there are no rituals or holidays or even words to legitimize them.

I feel glad to have found some happiness and some ability to contribute. I still struggle with that frightening specter of suburban life and the 1950s vision of parenthood it has hauled into the present day. I fear being hemmed in by the father role and excluded from the mother role, and I fear starting a family with someone who is succumbing to pressure and will only become miserable in due time. I fear having every day reduced by some percentage of time trapped in a car, shuttling myself and passengers from one box to the next, in a loop that goes on for ten, fifteen, twenty years.

But at the same time I wonder, maybe there's a way I can do this that works for me. I imagine joining parenting groups and finding local help with new friends. I picture living in some place that doesn't have a stupid lawn but does have a nice park nearby, and putting a child in a seat on the back of a bicycle and riding out for a picnic. I can see myself forming some alliance with neighbors, or moving closer to family, to cooperate on meals and shopping in some negotiated schedule that always puts four or five people around a table to keep things interesting. There's some non-suburban, non-isolating, non-straitjacket version of this course that I'm sure people around me are charting and I could potentially move from "uncle" to something more direct.

But should I? Especially at my age? And with my tendency to want to go on bike trips for a month at a time? Is the fact that I can't decide, proof in itself that I don't have the dedication to make it work?

The following is a long, semi-structured rant about parenting.

The following is a long, semi-structured rant about parenting. Pushing back against that pressure doesn't win friends. Doing something for your own sanity that has no visible benefit to your kids doesn't win approval. It’s true that once you have a child, your life generally should not be all about you anymore, but it’s just as true that your life should not be all about the kid, otherwise, why are you bothering?

Pushing back against that pressure doesn't win friends. Doing something for your own sanity that has no visible benefit to your kids doesn't win approval. It’s true that once you have a child, your life generally should not be all about you anymore, but it’s just as true that your life should not be all about the kid, otherwise, why are you bothering? I’ve met and enjoyed my time with women who were taller than me, hairier than me, louder than me, stronger than me, less nurturing than me, far less interested in children than me, and in some cases significantly more violent than me. Society has labeled them as deviants, and the difficulty they have had is not from being different, but from the label. Many of them are also parents, and have had to struggle to come to terms with the difference between the way they want to parent, and what the world expects. The majority of them are not comfortable accepting a role at the head of a stove, spending their time for years upon years constantly being the sole minder and guardian of infants who are - let’s be frank - terrible conversation, and often quite gross.

I’ve met and enjoyed my time with women who were taller than me, hairier than me, louder than me, stronger than me, less nurturing than me, far less interested in children than me, and in some cases significantly more violent than me. Society has labeled them as deviants, and the difficulty they have had is not from being different, but from the label. Many of them are also parents, and have had to struggle to come to terms with the difference between the way they want to parent, and what the world expects. The majority of them are not comfortable accepting a role at the head of a stove, spending their time for years upon years constantly being the sole minder and guardian of infants who are - let’s be frank - terrible conversation, and often quite gross. It baffles me that people consistently tell me that their happiest family memories come from times when the extended family was involved, whether for a holiday, or a vacation, or just an extended visit, and yet we have all convinced ourselves, that the only true route to creating the next generation is to hide exactly two people in their own structure, with a collection of personal appliances, located in some arbitrary location anywhere in the country regardless of how far it is from uncles, aunts, grandparents, and so on. As if, sure, it takes a village, but any old village will do, and what matters is the house with the fence and the driveway, not the presence of diverse and loving people who know your collective history and have charted a dozen different paths to happiness that you can draw from. Paths that include being an aunt or a godmother and so on, when not a parent directly.

It baffles me that people consistently tell me that their happiest family memories come from times when the extended family was involved, whether for a holiday, or a vacation, or just an extended visit, and yet we have all convinced ourselves, that the only true route to creating the next generation is to hide exactly two people in their own structure, with a collection of personal appliances, located in some arbitrary location anywhere in the country regardless of how far it is from uncles, aunts, grandparents, and so on. As if, sure, it takes a village, but any old village will do, and what matters is the house with the fence and the driveway, not the presence of diverse and loving people who know your collective history and have charted a dozen different paths to happiness that you can draw from. Paths that include being an aunt or a godmother and so on, when not a parent directly.

"Well, it's always been difficult for adults," I said. "The solution last century was lots of singles-only clubs and vacations and mixers, and they were always portrayed as these dank things full of people who were either a little too desperate, or somewhere on the creepy scale. But now the internet has blown that all up. It's created a renaissance for older people to find each other and connect -- even to connect in person."

"Well, it's always been difficult for adults," I said. "The solution last century was lots of singles-only clubs and vacations and mixers, and they were always portrayed as these dank things full of people who were either a little too desperate, or somewhere on the creepy scale. But now the internet has blown that all up. It's created a renaissance for older people to find each other and connect -- even to connect in person." It's fun being an uncle. I'm enjoying the mildly subversive side of it. Drawing my nephews out of their shells, throwing him into slightly challenging situations... Or just hanging around with them listening to their weird observations...

It's fun being an uncle. I'm enjoying the mildly subversive side of it. Drawing my nephews out of their shells, throwing him into slightly challenging situations... Or just hanging around with them listening to their weird observations... It's a conundrum. That which you focus on, you will have more of. And some things are only available to us for a limited time.

It's a conundrum. That which you focus on, you will have more of. And some things are only available to us for a limited time. Who is the man I fear?

Who is the man I fear? Sometimes I think it's just because the connection is always more tenuous than it feels, because it's with a person who is not integrated with my daily life at all. They can't help but be crowded out by all the things I already do, that don't involve them.

Sometimes I think it's just because the connection is always more tenuous than it feels, because it's with a person who is not integrated with my daily life at all. They can't help but be crowded out by all the things I already do, that don't involve them.