A few things about a few books

Sep. 22nd, 2014 11:29 amA bit darker and more thrilling than earlier entries in the series, with just a handful of laugh-out-loud moments, which is a disappointment only if you’re comparing this to Pratchett’s usual hilarious work. I’d still give it a 7 out of 10.

Shattered Dreams: My Life As A Polygamist’s Bride, by Irene Spencer (2007)

For a while I was keen to read about harrowing experiences in organized religion, and this was my window into the not-so-distant past of the Mormon church. The poverty, humiliation, and mental manipulation of the protagonist - and most of the other women she knew - at the hands of what were basically religiously glorified and sanctioned sexual predators, was fascinating and appalling, like a bad dream that defies expectations by getting worse and worse, without ever actually waking you up.

Unfortunately this book sags in the middle when Irene resigns herself to fate, on a destitute ranch somewhere in Mexico, and marks year after year of her passing life by pumping out children for her sleazeball of a husband. I stopped reading it after one too many pauses where I had to yell out to the quiet room: "What is wrong with you, woman? Stand up for yourself! Emancipate yourself! Recognize what your own choices are leading you into!"

This gets a 5 out of 10. It certainly didn’t do Irene any credit that she was only freed from the tyranny of this evil bastard when he died in a car accident. She stuck with him to the end, even though all she ever got from him was a sack-cloth dress, and rape.

The Long War, by Terry Pratchett and Stephen Baxter (2014)

Okay, so now we get the idea. Pratchett and Baxter are using this series as a sandbox for a bunch of tenuously connected alternate-Earth stories. Interesting, but, they uncover and begin exploring so many mysteries that I fear this is going to turn into a literary version of the Lost TV show, where you’re drawn more and more into the author’s apparent grand plan, eagerly guessing how it will all fit together, only to find out that there was never any grand plan at all, and the things that don’t fit together "yet" just don’t fit together, period.

So I tried to take this as an anthology. In that context, it’s still a pretty good read. 6 out of 10 snarling dog-people up.

Banished, by Lauren Drain (2013)

Continuing my religious kick. An interesting look into the ugly inner circle of the Westboro Baptist Church. As you’d expect, it’s populated by sociopaths and sycophants, and the pathetic children they’ve either spawned or adopted. Lauren was lucky enough to foster a few connections to the outside world and she escaped. An insightful and gossipy read. 6 out of 10.

The Clockwork Scarab by Colleen Gleason (2013)

I know it sounds strange to say, and it’s clearly my own fault for choosing the reading list I do, but it’s refreshing to read a fantasy novel with young women as the main characters that was written by a young woman. I can’t give any itemized account of differences, and even if I attempted to it would just invite accusations of gender stereotyping, but there was something I really enjoyed here, in this blend of lighthearted adventure, and enthusiastic digressions over wardrobe and setting, and the lack of frivolous "grit" or a tiresome "tragic past".

The ending was inconclusive, but I didn’t care - I was eager to spend another series of afternoons with these characters dashing about their pastiche alternate world. 7 steampunk rivets out of 10.

Naked In Baghdad by Anne Garrels (2004)

A first-hand account of the opening of the recent Iraq war by a tough-as-nails correspondent. An efficient and honest you-are-there narrative that doesn’t contain much direct philosophizing or introspection, but eagerly invites it in the reader. Just what you’d expect from a journalist, actually. 7.5 loose bricks out of 10.

Bryant And May #10: The Invisible Code by Christopher Fowler (2013)

Another good entry in the series. Chases, interviews, guided tours of English architectural history, and plenty of bon-mots from the irascible Arthur Bryant. A solid competitor to Terry Prachett for reading pleasure. 8 hidden needles with mysterious poison out of 10.

Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt by Michael Lewis (2014)

This book takes what is potentially a very boring, dry subject, and makes it entertaining by focusing on the characters involved. I’m glad I read it, even if all it did was confirm the level - and nature - of the digital corruption that I already assumed was infecting the world stock market. In a nutshell: Insider trading is now built-in, and the trading platforms exist mainly to provide an easy method for useless middle-men to extract money from the process.

This Book Is Full Of Spiders by David Wong (2013)

Very entertaining, in a B-movie sort of way. If you want more of the vibe of Big Trouble In LIttle China and Bill And Ted, with a couple of genuinely horrifying scenes thrown in for variety, check this out. Sometimes the author indulges his philosophical side too much, but he makes up for it with excellent humor.

The Long Mars by Terry Pratchett and Stephen Baxter (2014)

About half of this book concerns a splinter group of humanity called The Next, young super-geniuses who, as one reviewer nicely puts it, "reminded me unfavorably of my grandson's smart-aleck geek buddies when they were in high school."

I didn’t care for that half. The Next were a nonsensical mashup of physiology-defying intellectual powers and ridiculous adolescent angst. I assume we’ll learn their fate in future sequels, but I’m not looking forward to it. It’s hard to get invested in characters when their motives don’t make sense.

The other half was an exploration of the titular long Mars, and it was pretty darned interesting, even though a lot of it felt like recycled material from Stephen Baxter’s other work. The guy is in love with the early Russian and U.S. space programs, and he clearly hijacked this series, fast-forwarding the timeline past a large chunk of the Long Earth’s new history just to make the leap to Mars feel plausible. He also distorted the basic premise of "stepping" way out of shape, by declaring that a human could "step" between worlds and casually bring along an entire two-man glider, with luggage and passenger, plus a wind-envelope of unknown size all around the vehicle. How? Well, because we can’t explore the Long Mars otherwise, that’s how.

What a cheat.

Mary O’Reilly Book 1: Loose Ends by Terri Reid (2012)

This had a promising beginning, but somewhere in the second half I lost my grip on the author’s idea of "ghosts" and what they were supposed to be. Wandering souls, or just unresolved fragments of people? Corporeal or not? Able to appear to anyone, or just the "sensitive"? Stuck in one place, or able to travel? Can they make noise? Do they know what they need, or not? It seemed to change based on narrative convenience. Plus, if the villain were any more one-dimensional, he would vanish entirely.

4 out of 10 bloody handprints up.

Life On Mars: Tales from the New Frontier (2011)

These stories were all excellent, and were enhanced further by the "about the author" and "author’s note" sections that came after each one. I was impressed by the socio-political content as well. The authors not only asked "what would humanity do to Mars" but "what would Mars to do humanity" and they came up with some fascinating answers. 7 out of 10 atmosphere-skimming surf pods up.

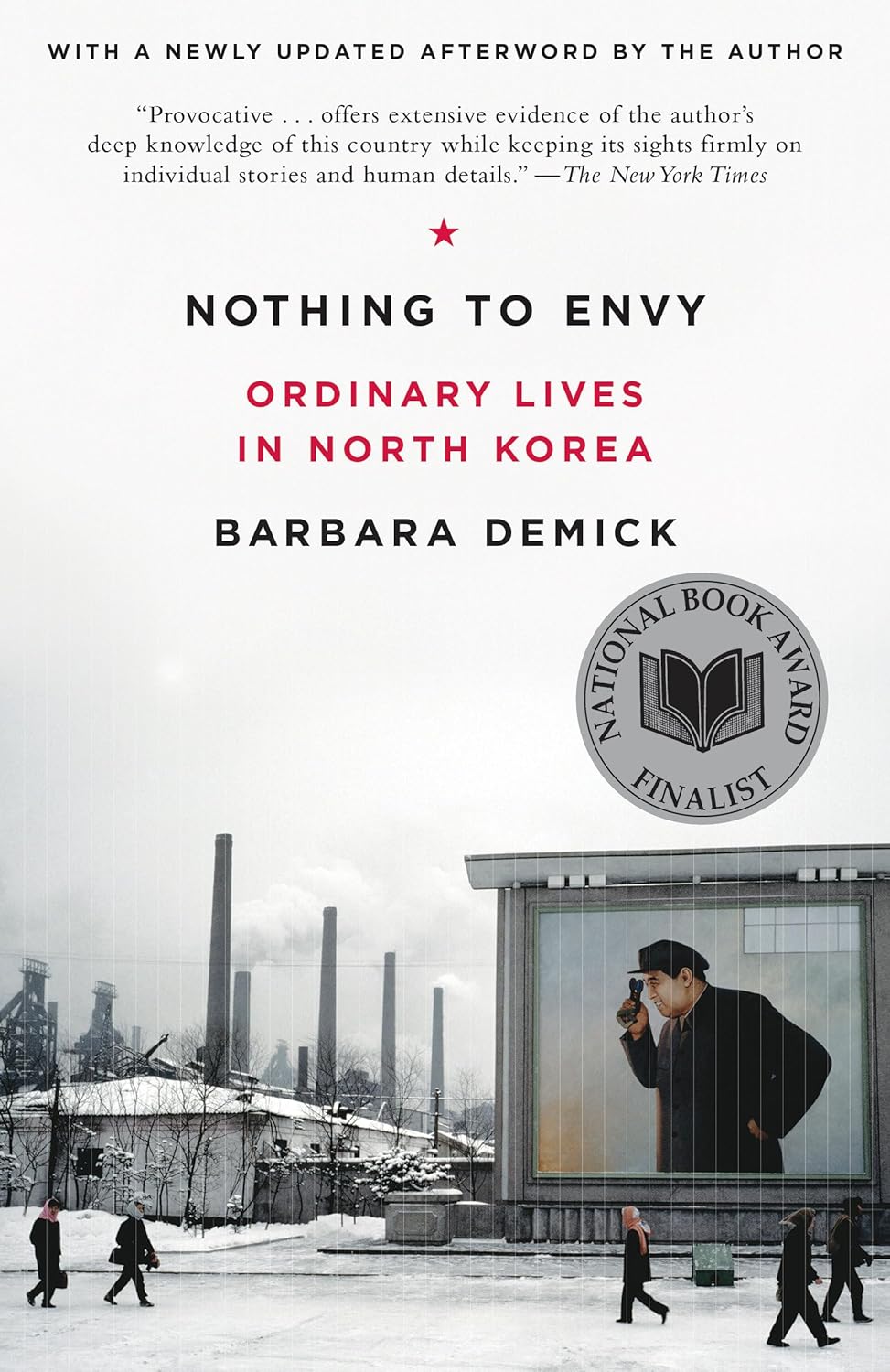

I’m a 38-year-old dude. By common wisdom I should have a very stoic appearance, generally. But I had to pause in reading this book, put it down, and sit there and cry for a little while. Not once, but four times. At least four times. This interwoven stories in this book astounded me, revolted me, and humbled me. At first I had a little bit of trouble keeping the interview subjects straight because the narrative jumps between them, but it didn’t matter that much, since the effect - and the possible intention of the book - is to blur the experiences of these people together, into one highly detailed tapestry of political disenfranchisement, psychological abuse, and appalling and abject poverty.

I’m a 38-year-old dude. By common wisdom I should have a very stoic appearance, generally. But I had to pause in reading this book, put it down, and sit there and cry for a little while. Not once, but four times. At least four times. This interwoven stories in this book astounded me, revolted me, and humbled me. At first I had a little bit of trouble keeping the interview subjects straight because the narrative jumps between them, but it didn’t matter that much, since the effect - and the possible intention of the book - is to blur the experiences of these people together, into one highly detailed tapestry of political disenfranchisement, psychological abuse, and appalling and abject poverty.